National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act aims at enhancing the livelihood security of people in rural areas by guaranteeing hundred days of wage-employment in a financial year to a rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

Implemented by?

Implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development is the flagship programme of the Government that directly touches lives of the poor and promotes inclusive growth.

Aim--

The Act aims at enhancing livelihood security of households in rural areas of the country by providing at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

Timeline and Phases---

The Act came into force on February 2, 2006 and was implemented in a phased manner.

In Phase one it was introduced in 200 of the most backward districts of the country.

It was implemented in an additional 130 districts in Phase two 2007-2008. As per the initial target, NREGA was to be expanded countrywide in five years.

However, in order to bring the whole nation under its safety net and keeping in view the demand, the Scheme was extended to the remaining 274 rural districts of India from April 1, 2008 in Phase III.

Features--

National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) is the first ever law internationally, that guarantees wage employment at an unprecedented scale. The primary objective of the Act is augmenting wage employment. Its auxiliary objective is strengthening natural resource management through works that address causes of chronic poverty like drought, deforestation and soil erosion and so encourage sustainable development. The process outcomes include strengthening grassroots processes of democracy and infusing transparency and accountability in governance.

How it helps Decentralization?

With its rights-based framework and demand driven approach, National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) - marks a paradigm shift from the previous wage programmes. The Act is also a significant vehicle for strengthening decentralization and deepening processes of democracy by giving a pivotal role to the Panchayati Raj Institutions in planning, monitoring and implementation. Unique features of the ACT include, time bound employment guarantee and wage payment within 15 days, incentive-disincentive structure to the State Governments for providing employment as 90 per cent of the cost for employment provided is borne by the Centre or payment of unemployment allowance at their own cost and emphasis on labour intensive works prohibiting the use of contractors and machinery. The Act also mandates 33 percent participation for women. Over the last two years, implementation trends vindicate the basic objective of the Act.

Figures--

Increasing Employment Opportunities: In 2007-08, 3.39 crore households were provided employment and 143.5 crore person days were generated in 330 districts. In 2008-2009, upto July, 253 crore households have been provided employment and 85.29 crore person days have been generated.

Enhancing Wage Earning and Impact on Minimum Wage: The enhanced wage earnings have lead to strengthening of the livelihood resource base of the rural poor in India; in 2007-2008, more than 68% of funds utilised were in the form of wages paid to the labourers. In 2008-2009, 73% of the funds have been utilized in the form of wages.

Increasing Outreach to the poor: Self targeting in nature, the Programme has high works participation of marginalized groups like SC/ST (57%), women (43%) in 2007-2008. In 2008-2009, upto July, the participation is SC/ST (54%) and women (49%), strengthening Natural Resource Base of Rural India: In 2007-08, 17.88 lakh works have been undertaken, of which 49% were related to water conservation. In 2008-2009, upto July, 16.88 lakh works have been undertaken, of which 49% are related to water conservation.

Financial Inclusion of the poor: The Central government has been encouraging the state governments to make wage payment through bank and post office accounts of wage seekers. Thus far, 2.9 crore (upto July '08) NREGA bank and post office accounts have been opened to disburse wages. The Ministry is also encouraging the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) - workers to obtain insurance under Jan Shri Bima Yojana.

Initial evidence through independent studies indicates enhancement of agricultural productivity (through water harvesting, check dams, ground water recharging, improve moisture content, check in soil erosion and micro-irrigation), stemming of distress migration, increased access to markets and services through rural connectivity works, supplementing household incomes, Increase in women workforce participation ratios and the regeneration of natural resources.

The vision of the Ministry is enabling NREGA become a transformative vehicle of empowering local communities to enhance their livelihood security. The Ministry has taken several steps to ensure the Scheme is implemented effectively like encouraging decentralized participatory management, improving delivery systems and public accountability.

The Rozgar Jagrookta Puruskar award has been introduced to recognize outstanding Contributions by Civil society Organizations at State, District, Block and Gram Panchayat levels to generate awareness about provisions and entitlements and ensuring compliance with implementing processes.

Building Capacity to implement a demand driven scheme

To strengthen the capacity and give priority to the competencies required for effective planning, work execution, public disclosure and social audits the Ministry has been conducting training for NREGA functionaries, Thus far, 6.2 lakh PRI functionaries and 4.82 lakh vigilance and monitoring committees have been trained (upto July'08). The Central Government is also providing technical support in key areas of communication, training, work planning, IT, social audits and fund management at all levels of implementation to the state governments.

Using IT for reaching out and inclusion

Web enabled Management Information System (MIS) is one of the largest data base rural households through their engagement in National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) - . MIS places all critical parameters such as shelf of projects, sanctioned works, wage payments, number of days of employment provided and works under execution on line for easy public access. The data engineered software has been designed for cross verification of records and generation of alerts to support proactive response by management.

Evolving processes for transparency and public accountability

Monitoring and Evaluation: The Ministry has set up a comprehensive monitoring system. This year, 260 National Level Monitors and Area Officers have undertaken field visits to each of the 330 Phase I and Phase II districts at least once.

For effective monitoring of the projects 100% verification of the works at the Block level, 10% at the District level and 2% at the State level inspections need to be ensured.

Road Map for Further Strengthening of NREGA

Setting up of the Task force on Convergence: In order to optimize the multiplier effects of National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) , the Ministry has set up a Task Force to look at the possibility of convergence of programmes like National Horticulture Mission, Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana, Bharat Nirman, Watershed Development with NREGA. These convergence efforts will add value to NREGA, works and aid in creating durable efforts and also enable planned and coordinated public investments in rural areas.

NREGA & Union Budget 2010-11:

Apparently, the finance minister is not inclined to have given enough allocation to NREGA, the much-talked-about rural employment guarantee programme. Renamed Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, NREGA has completed four years of implementation during which it has been extended to all districts covering more than 45 million households.

Last year, Pranab Mukherjee allocated Rs.39,100 crore (INR 391,000 million) in his 2009-10 budget, marking an increase of 144% over 2008-09 budget. Surprisingly, in 2010-11 budget, the figure has been rounded off to nearest figure at Rs.40,100 crore (INR 401,000 million) and no explanation has gone into the budget for this static figure. It certainly indicates that the government seeks to cap the rural employment programme at this level. Otherwise, those who have worked for more than 15 days during the preceding financial year under the NREGA have been extended the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (insurance cover) under the budget which will benefit the below poverty line workers and their families in rural areas.

Critical Issues of NREGA, how they are addressed?

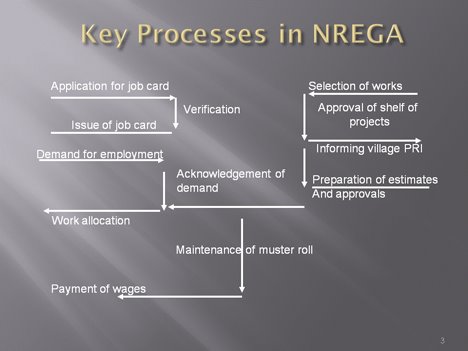

- Issues Related to Job Cards: To ensure that rural families likely to seek unskilled manual labour are identified & verify against reasonably reliable local data base so that nondomiciled contractor’s workers are not used on NREGA works . What is done for this problem? Job card verification is done on the spot against an existing data base and Reducing the time lag between application and issue of job cards to eliminate the possibility of rentseeking, and creating greater transparency etc. Besides ensuring that Job Cards are issued prior to employment demand and work allocation rather than being issued on work sites which could subvert the aims of NREGA

- Issues related to Applications: To ascertain choices and perceptions of households regarding lean season employment to ensure exercise of the right to employment within the time specified of fifteen days to ensure that works are started where and when there is demand for labour, not demand for works the process of issuing a dated acknowledgement for the application for employment needs to be scrupulously observed. In its absence, the guarantee cannot be exercised in its true spirit

- Issues Related to Selection of Works: Selection of works by gram sabha in villages and display after approval of shelf of projects, to ensure public choice, transparency and accountability and prevent material intensive, contractor based works and concocted works records

- Issues related to Execution of Works: At least half the works should be run by gram panchayats . Maintenance of muster roll by executing agency -numbered muster rolls which only show job card holders must be found at each work-to prevent contractor led works

- Issues related to measurement of work done: Regular measurement of work done according to a schedule of rural rates sensitive Supervision of Works by qualified technical personnel on time. Reading out muster rolls on work site during regular measurement -to prevent bogus records and payment of wages below prescribed levels

- Issues related to Payments: Payment of wages through banks and post offices -to close avenues for use of contractors, short payment and corruption

- Audit : Provision of adequate quality of work site facilities for women and men labourers Creation and maintenance of durable assets Adequate audit and evaluation mechanisms Widespread institution of social audit and use of findings

Current News

| Deshmukh to look into delinking NREGA from wages Act |

| BS Reporter / New Delhi January 21, 2011, 1:15 IST |

Senior Congress leader Vilasrao Deshmukh, who took charge today as the Union rural development minister, said he would look into the controversy over delinking the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), the government’s largest rural employment programme, from the Minimum Wages Act.

“I have to go into the matter, as I am not aware of the ministry’s position and the court rulings in the matter so far,” he said.

Yesterday, former Supreme Court Chief Justice J S Verma called delinking of the works programme from the Minimum Wages Act as unconstitutional and illegal, adding the apex court should take suo motu cognisance of the violation of multiple provisions of the Constutution by the government and defiance of court orders to delink NREGA wages from the Act.

The Hindu Article--- Dalits, the poor and the NREGA

Before tinkering with the NREGA in the name of reforms, the government must ensure that the foundations of the scheme are strengthened. No change should be introduced without a rigorous debate that centrally involves its primary constituents.

As the Union Ministry of Rural Development attempts to craft the architecture of what is being referred to as “NREGA 2,” the principles that constitute the basic foundation of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act must be kept in mind. The NREGA evolved out of a political response to a people’s movement and the articulated needs of rural workers. It put the people’s right to seek work in a legal framework, and approached development through the economic and social empowerment of the poor and the marginalised. The focus was clear: work must be provided on demand. The assets created should benefit the poorest and most marginalised communities first. The work itself should create and sustain favourable conditions for providing minimum wage employment in a transparent and accountable manner. Plans, and even new programmes, should be suggested and endorsed by the people. With a large increase in fund flow, the gram sabha and the panchayat is finally in a position to actually build participatory democracy, and people’s planning can be developed, as Kerala did along with fund devolution.

Despite all the criticism with respect to corruption and leakages, the NREGA has actually drawn attention to the weaknesses of the delivery mechanism. And it has made a host of different sets of people apply their collective skills to repair them. It is true, however, that the achievements of the NREGA have been uneven: in many States even the job cards are yet to be properly issued. Its foundations still being weak, any immediate change must not burden the fragile success, and must strengthen its basic structure. Most important, no change should be introduced without rigorous debate, centrally involving its primary constituents.

Unfortunately, the first change was slipped through on July 22, 2009, when Schedule I of the NREGA was amended to allow the “provision of irrigation facility, horticulture plantation, and land development facilities to land owned by households belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes or below poverty line families or to beneficiaries of land reforms or to the beneficiaries of the Indira Awaas Yojana of the Government of India, or that of the small or marginal farmers as defined in the agriculture debt waiver and debt relief Scheme 2008.” (the amendments made are marked in italics). The definition of small and marginal farmer used here implies that anyone who owns up to five acres of arable land (over 80 per cent of farmers come in this category) will be eligible for assets on their land.

By removing the focus of such subsidies from Dalits and the poor, this deceptively benevolent looking amendment could fundamentally change the course of the NREGA. Yet it came about with no public consultation or debate: in fact without even placing the matter before the Central Employment Guarantee Council (CEGC). What is its potential impact?

With all its shortcomings and failings, the limited benefit provided by the NREGA has been an important support structure for the poorest and most marginalised rural communities. Wage work has been open to all those who offer to do casual manual work on eight categories of work — most of which are designed to strengthen the natural resource base of those who are most dependent on such community assets for their livelihoods.

At a meeting with a group of farmers including small and marginal farmers who work on NREGA worksites, there was unanimous agreement that the amendment would place the controls of the NREGA in the hands of the landed peasantry. Another apprehension that was strongly articulated was the potential disintegration of the strong transparency and accountability provisions that have been woven into the NREGA, as collective work on community land is replaced by work on individual landholdings. Dalits and the below poverty line group, however, had a sharper and personalised reaction. One of them said: “We have just begun to get something out of this Act, and it seems everyone wants to find ways of taking it away from us. Dalits and the poorest farmers will be pushed out, and the landless will be left developing assets for others.”

So far, only a fraction of poor and Dalit farmers have been sanctioned works. There is no justification to include others, and move to the second generation when the priority group is still to be covered.

At a meeting at Vigyan Bhavan in Delhi on August 20, Union Minister of Rural Development C.P. Joshi said the Ministry welcomed “discussion, debate and dissent.” Having received objections, he made the welcome announcement that the amendment would be kept in abeyance and re-examined, keeping in mind its potential impact on Dalits and the poor. However, the amendment itself needs to be withdrawn or suspended immediately, at the least, till lands of the first category are saturated.

One of the arguments used against the NREGA is that it has made farming difficult because farm labour have to be paid higher wages. This complaint is in fact one of the strongest endorsements the NREGA could receive. It is a law designed to support the poorest, and this criticism indicates that the NREGA has increased the bargaining power of rural labourers.

What about the farmer’s problem? The severe crisis in the agricultural sector must be addressed, and the viability of farming in India ensured. There are a slew of measures that are needed to ameliorate distress and increase the vibrancy of farming. These should include better support prices, more rational policies in international trade, special programmes and direct subsidies for agricultural revival including the building of farm ponds on every farm, better credit policies and effective crop insurance. Questions of credit, trade, and technology must be re-examined keeping the farmer’s long-term interests in mind. However, subsidising farmers through lower wages for agricultural labour, or transferring a share of resources meant for those who are worst-off in rural India, is the most unjust way to help the Indian farmer. The legitimate concerns of the farmers need to be separately addressed. The fragile success of an employment programme cannot bear the burden of lifting the entire rural economy out of the morass.

At a time when the spectre of drought looms large, the primary focus must be on providing work and wages on time. The NREGA is the first law in the country that put economic and social rights in a legal framework. Establishing such an alliance between the poorest citizen and the state on these most basic components, is the real blueprint of the NREGA.

We need to make sure this foundation is strong, and then carefully begin to construct NREGA II. There are strong legal provisions within the law that a citizen can initiate to demand work on 15 days, payment of wages in 15 days, and redress of grievances within seven days. In case of failure, workers can demand unemployment allowance, compensation and imposition of penalties.

Instead of trying to tinker with second-generation reforms, the government needs to first demonstrate that it can ensure an effective response to these demands across the country. An alliance between the ordinary citizen and the state is the roadmap of not just the NREGA, but of democratic governance.

TOI--What's in NREGA for the middle class

Despite its seminal success in beginning a process of addressing issues of poverty, starvation and empowering the poor, the MGNREGA needed a general election to breathe life into it. However, the disproportionate influence of the middle class on social sector policy has led to the same set of pre-election prejudices resurfacing.

"What use is the MGNREGA to the economy at large?" asks the businessman, one eye fixed apprehensively on the share market. Meanwhile, the policy maker "crunches figures" to see whether the 8 ½ can become nine or 10 this year, and sundry young people aspire to pass "CAT" to settle abroad?

We have even forgotten how rural markets in India survived the global economic downturn. In Rajasthan, even cynical politicians and administrators admit that the drought of 2009 passed off without huge rural unrest due to MGNREGA. We have become so short-sighted that we think that anything we do not immediately and directly benefit from must be a waste.

It is important to address the three biggest issues raised to discredit the act — human resources, corruption, and productive assets.

MGNREGA has given people, the largest economic resource in our country, some amount of work, and plenty of dignity. In state after state, workers have testified that guaranteed employment has enabled them to fight many battles including a system of oppression where they have no choice but to acquiesce to forced labour, indebtedness and the indignity of having to beg for survival. The unemployed are becoming workers, and workers are raising issues of citizenship.

There is no doubt that corruption threatens and undermines the MGNREGA, but it is being fought with courage and determination by some of the most disadvantaged people in our country. In fact, it has given birth to more anti-corruption activists than any other programme in India. In guaranteeing provisions for transparency and accountability, it has empowered the ordinary worker to question and demand answers from the local power structure. Our battles against corruption in the patently wasteful Commonwealth Games could greatly benefit by learning from the anti-corruption struggles of MGNREGA workers. We might then figure out how to fight the corruption that permeates every part of our political and administrative structure.

And what about assets? The popular image of MGNREGA is of millions of people across the country busy digging holes and filling them up. Several-thousand water harvesting structures have been built in the most eco friendly manner possible, rural roads have connected some of the poorest, most inaccessible hamlets, millions of dalits, land allottees and BPL families have converted wasteland into productive plots through MGNREGA work.

Without meaningful evaluation of the utility of the assets created, policy makers make assertions about useless work. If it benefits the rich, an asset is called infrastructure. If it is of use to the poor, it is the dole. Undoubtedly, all of this could have been done better, more efficiently, with better planning and implementation. If only the policy makers and the implementation agencies had carried out this mandate, including the initiation of a bottom-up effort to appropriately expand the category of permissible works.

Why can't the fantastically gifted folk artists and singers become music tutors for a hundred days a year at primary schools in their area instead of digging sand in the desert?

Can the differently-abled not be encouraged to do work appropriate to their abilities, as long as they engage in "productive employment at minimum wages"?

Can parts of the country with a dearth of public land, not be allowed to design and evolve their own set of appropriate works?

The truth is that the failures of the MGNREGA are the handiwork of the powerful elite and an entrenched self-serving bureaucracy. Workers are paying the price and landmark legislation is being undermined through the failure of policy makers and administrators to do their job. Finally the country will pay the price in fundamental, basic ways.

Aruna Roy is a member of the National Advisory Council

"What use is the MGNREGA to the economy at large?" asks the businessman, one eye fixed apprehensively on the share market. Meanwhile, the policy maker "crunches figures" to see whether the 8 ½ can become nine or 10 this year, and sundry young people aspire to pass "CAT" to settle abroad?

We have even forgotten how rural markets in India survived the global economic downturn. In Rajasthan, even cynical politicians and administrators admit that the drought of 2009 passed off without huge rural unrest due to MGNREGA. We have become so short-sighted that we think that anything we do not immediately and directly benefit from must be a waste.

It is important to address the three biggest issues raised to discredit the act — human resources, corruption, and productive assets.

MGNREGA has given people, the largest economic resource in our country, some amount of work, and plenty of dignity. In state after state, workers have testified that guaranteed employment has enabled them to fight many battles including a system of oppression where they have no choice but to acquiesce to forced labour, indebtedness and the indignity of having to beg for survival. The unemployed are becoming workers, and workers are raising issues of citizenship.

There is no doubt that corruption threatens and undermines the MGNREGA, but it is being fought with courage and determination by some of the most disadvantaged people in our country. In fact, it has given birth to more anti-corruption activists than any other programme in India. In guaranteeing provisions for transparency and accountability, it has empowered the ordinary worker to question and demand answers from the local power structure. Our battles against corruption in the patently wasteful Commonwealth Games could greatly benefit by learning from the anti-corruption struggles of MGNREGA workers. We might then figure out how to fight the corruption that permeates every part of our political and administrative structure.

And what about assets? The popular image of MGNREGA is of millions of people across the country busy digging holes and filling them up. Several-thousand water harvesting structures have been built in the most eco friendly manner possible, rural roads have connected some of the poorest, most inaccessible hamlets, millions of dalits, land allottees and BPL families have converted wasteland into productive plots through MGNREGA work.

Without meaningful evaluation of the utility of the assets created, policy makers make assertions about useless work. If it benefits the rich, an asset is called infrastructure. If it is of use to the poor, it is the dole. Undoubtedly, all of this could have been done better, more efficiently, with better planning and implementation. If only the policy makers and the implementation agencies had carried out this mandate, including the initiation of a bottom-up effort to appropriately expand the category of permissible works.

Why can't the fantastically gifted folk artists and singers become music tutors for a hundred days a year at primary schools in their area instead of digging sand in the desert?

Can the differently-abled not be encouraged to do work appropriate to their abilities, as long as they engage in "productive employment at minimum wages"?

Can parts of the country with a dearth of public land, not be allowed to design and evolve their own set of appropriate works?

The truth is that the failures of the MGNREGA are the handiwork of the powerful elite and an entrenched self-serving bureaucracy. Workers are paying the price and landmark legislation is being undermined through the failure of policy makers and administrators to do their job. Finally the country will pay the price in fundamental, basic ways.

Aruna Roy is a member of the National Advisory Council

No comments:

Post a Comment